Digitalt AiR: The Boundless Platform – Unfolding Print

The name The Boundless Platform – Unfolding Print comes from the idea that printmaking is a lot about sharing experiences in the studio and through processes finding new paths and directions. However, we do not want to limit ourselves only to the physical space, but to be able to facilitate the exchange of knowledge and gain new insights into how printmaking change and develop in different places and contexts. The meaning of Unfolding Print is that there is much more to the possibilities of printmaking than the scene we see here in the Nordics, and our task as a museum for contemporary printmaking is to openly explore and highlight its variety and history.

Alongside artists, activists, researchers, graphic designers, programmers, we would like to explore contemporary printmaking through digital tools as a medium.

Here we see the opportunity to bring in more perspectives and narratives by directing this digital platform to artists who have knowledge of a norm-critical approach and an understanding of printmaking history outside the Western canon.

The platform leads with questions such as:

- What discussions and creations are taking place in the printmaking art scene around the world?

- What topics, social questions are relevant now in different places and contexts and how are they seen and discussed through printmaking?

Grafikens Hus, which is a center for fine art printmaking, can be the one that intertwines different initiatives that work with printmaking in different ways. There are many who work with printmaking around the world, and Grafikens Hus wants to be able to facilitate a digital meeting place that is in process and in transformation. Together with artists and other actors who could be relevant, we invite different collaborations to co-create a digital platform in the form of, among other things, digital artist in residency, digital take overs etc.

All new exhibitions, documentations, art pieces and material part of The Boundless Platform will be gathered in this space. The Boundless Platform – unfolding print have English as the main language.

We sincerely hope you will enjoy following this journey with us and invite you to explore printmaking from the digital realm.

Are you interested in being part of The Boundless Platform? Look out for our open calls, or contact us at info@grafikenshus.se

CREDITS:

Design: Taurai Mtake

Programming: Rickard Westerlind

Grafikens Hus team: Nina Beckmann, project leader, Anna Jönsson, project leader, Anna Henriksson, communication and Emma Dominquez, art educator.

Initiator & project leader: Amanda Ferrada (2021-2022)

Coordinator: Nilo Amlashi (2023)

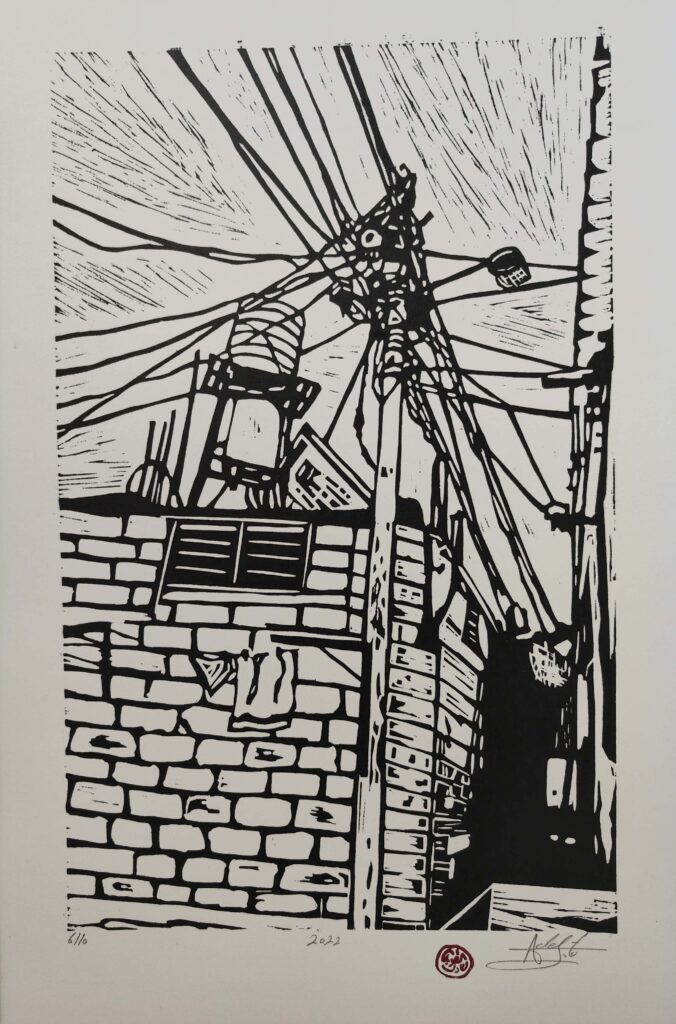

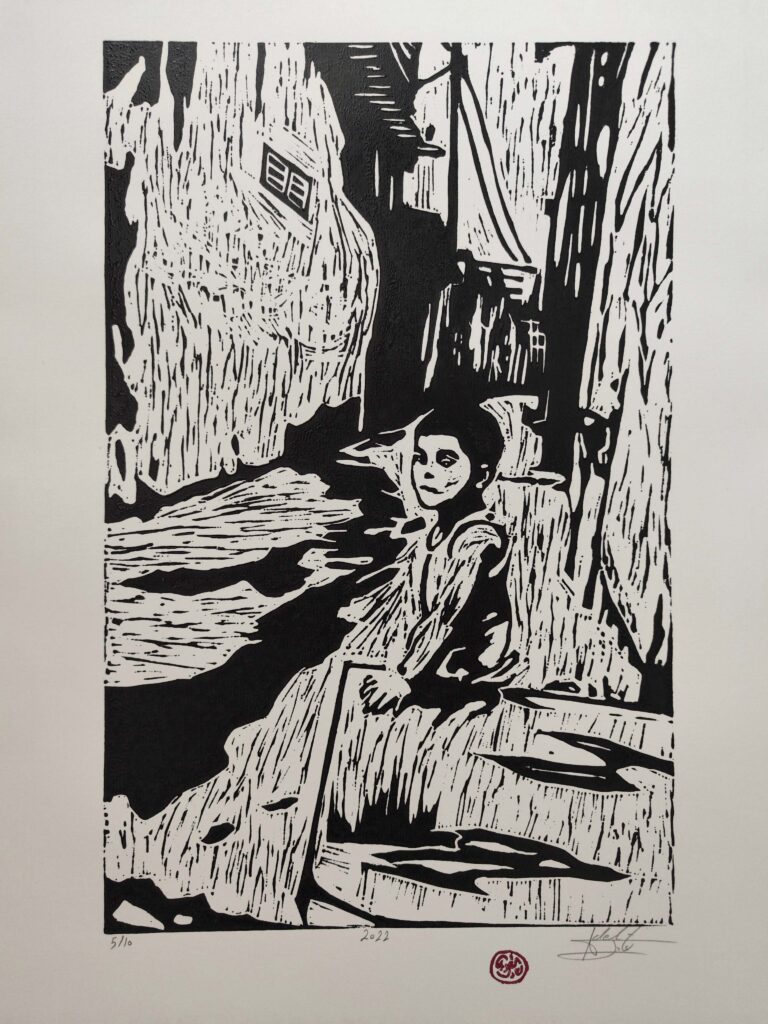

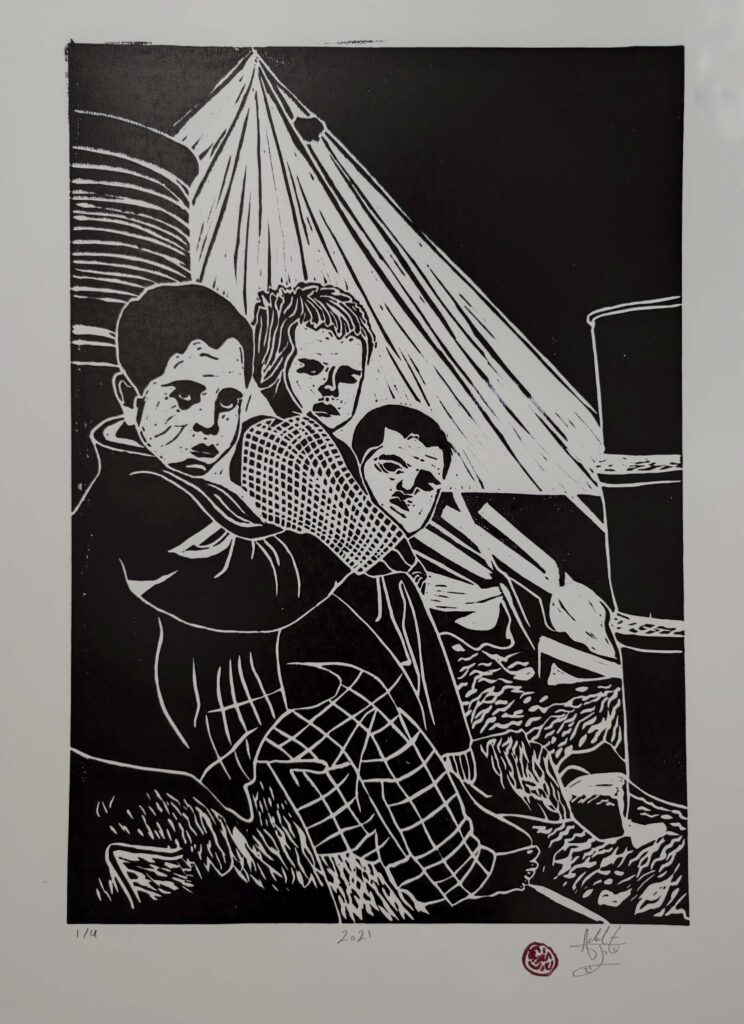

Artist’s bio

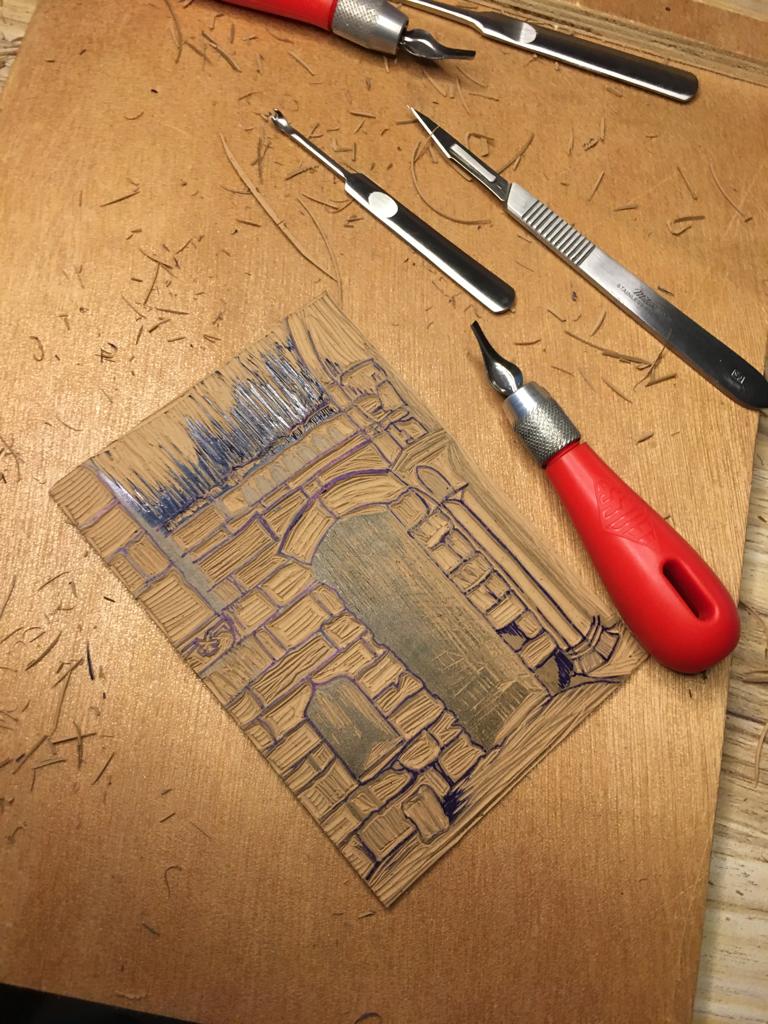

Adel Al-Taweel was born in 1995 in Nuseirat Refugee Camp in Gaza, Palestine. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the Institute of Fine Arts at Al-Aqsa University in Gaza, then continued his studies in France, where he obtained a degree in art history from the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts in Paris. He is a member of the Union of Palestinian Artists. Since arriving in France in April 2024, he has been living in Paris, where he continues to develop his artistic practice. His work tackles humanitarian and social issues, and draws on archives and memory to document the past and present and imagine the future. His artworks take the form of multi-media installation, sculpture, engraving and printing, which he often uses to address contemporary issues such as Palestinian identity and the experience of life in refugee camps. He also works in public spaces to address issues of displacement and immigration through his research on the ideas of home and belonging.

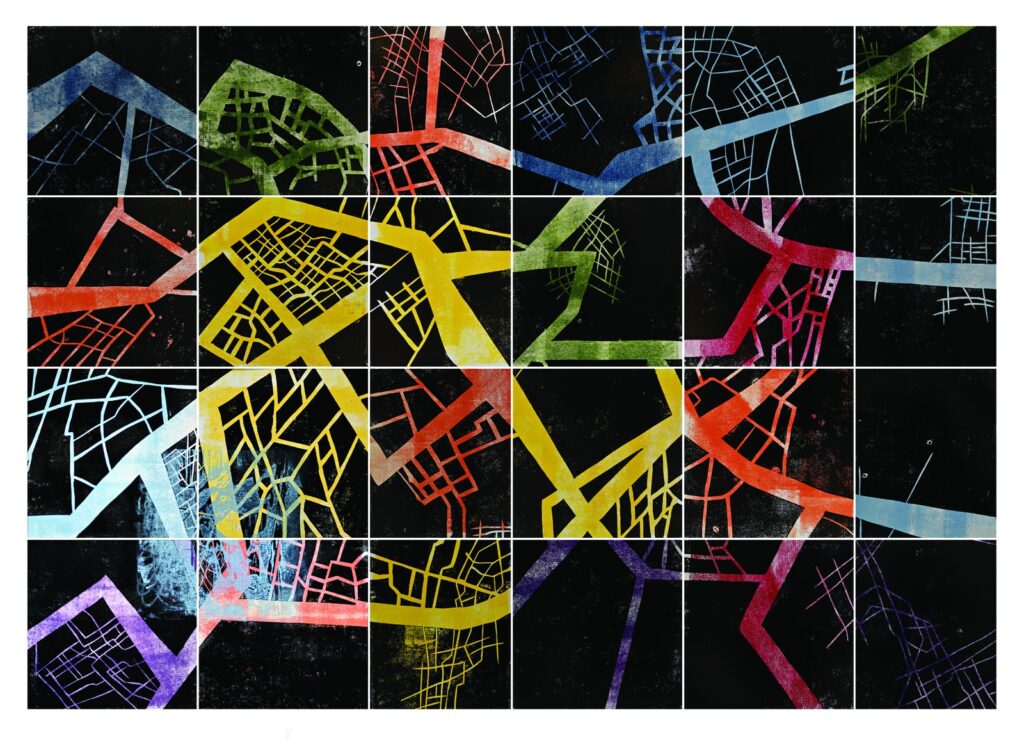

In an art project in Vallorcine, France, in the heart of the Alps, he sought to understand and analyse maps after wars and explore their evolution in order to reimagine the geographical transformations of different regions, continuing his interest in spatial and human memory. Al-Taweel has participated in numerous local and international group exhibitions and contributed to research symposia and international workshops alongside global artists such as Nicolas Combaud and Hakim Jamain. In addition to his own artistic work, he was also featured in the film “Who Is Still Alive,” (2025) a natural extension of his artistic and humanitarian commitment.

Thank you to Mariam Elnozahy, Artistic Director at Konsthall C, for curating this digital residency and for the collaboration.

Photo credits: Courtesy the artist/Adel Al-Taweel

Artist’s bio

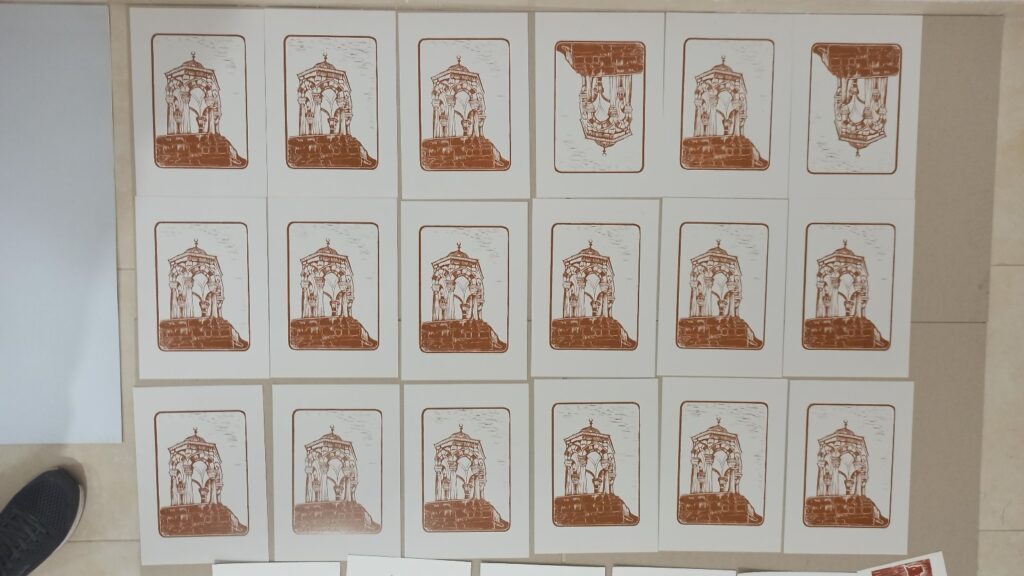

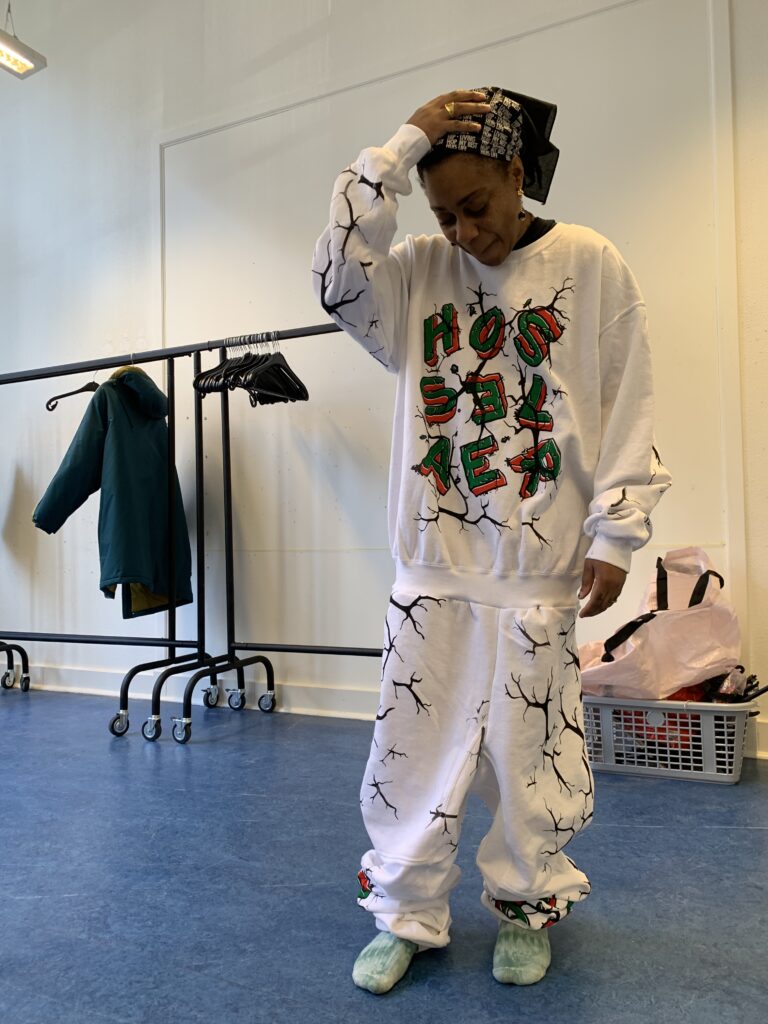

Longest Night is an artist-run screen printing workshop, gallery and shop in Kortedala, Sweden. We print and publish graphic art in collaboration with the most interesting artists we know. We also organize exhibitions, workshops, residencies and other events where people and art meet. We aim to be a vibrant place for production, participation and creativity in our local residential area in Eastern Gothenburg.

As artists, we strive for independence, self-sufficiency and collective utilization of resources. Our craftsmanship gives us the means to reproduce art without intermediaries, to work with recycling and upcycling of textiles and clothing, and to create printed matter in all possible formats and forms. We collaborate with underground stars and outsiders, self-taught and professionals, experienced graphic artists and those making their first attempts at graphic production. Our workshop is open to local artists and their ideas, we share knowledge, resources and contacts and we regularly organize free creative workshops for children and young people.

Foto fr.v övre raden: David Soda, Josip Bolonic, Josip Bolonic. Nedre raden fr.v.: David Soda, Anna Ehrlemark, Josip Bolonic.

During the “Digital Takeover”, we will be posting about our usual activities and process of making prints as a collective. We will be showing photos and videos of our weekly Thursday gatherings, our base of operations, the work we have been producing, how we make prints of various sizes in a small space without a press, and how we use our prints.

We will also show the research processes of researching for our new pieces and of making “Introduction to Woodblock Prints for Action,” a zine which we plan to self-publish. We also have in storage the works of our friends who are engaged in collective printmaking in different parts of Asia, so through them we would like to share with you how big and diverse the network of printmaking collectives has grown in Asia.

Artist’s bio

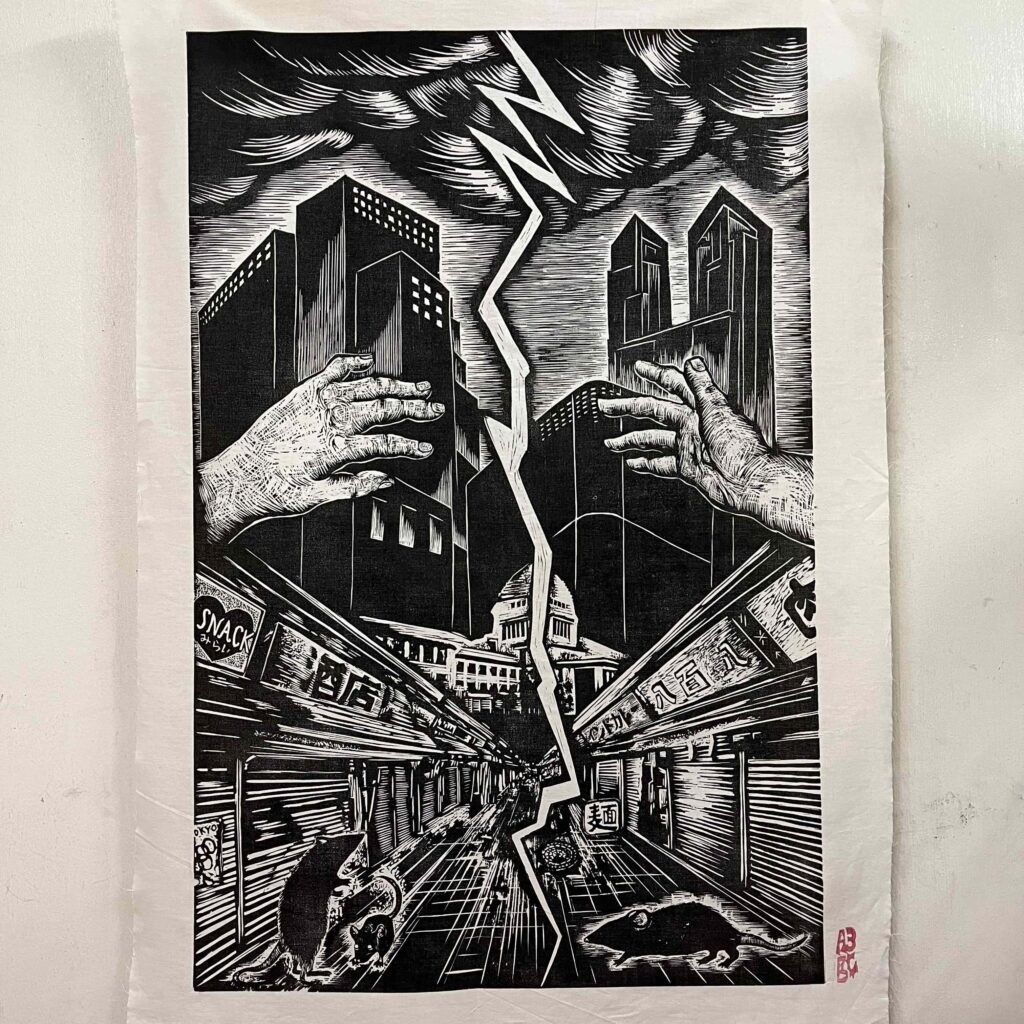

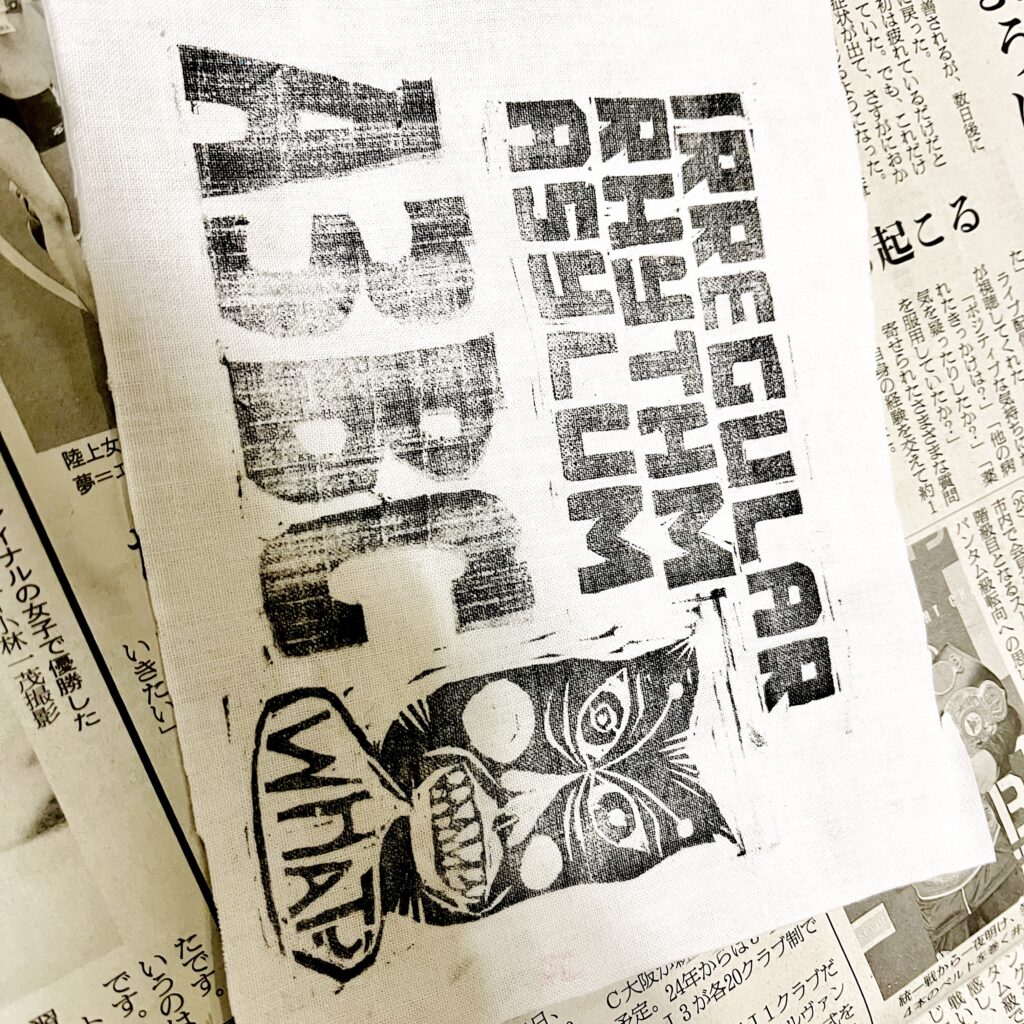

A3BC (Anti-War, Anti-Nuclear and Arts of Blockprint Collective) formed in the summer of 2014 at IRREGULAR RHYTHM ASYLUM (IRA), an infoshop in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Our foundation was inspired by woodblock print collectives in Southeast Asia, such as Pangrok Sulap, Taring Padi as well as Marginal. We have learned a lot about the skills and joys of collective printmaking from our friendship with these collectives. Although A3BC stood for “Anti-War”, “Anti-Nuclear power” and made artwork with such themes in the beginning, we now address a wider range of social justice issues with our woodblock prints.

”Currently in Japan, we have been invited to attend the exhibition: Debordering Woodcut Printmaking Practice in Inter-Asian Context at Tokyo University of Art. Afterwards, we will be in Koganecho for a mini-workshop and exhibition. We will conclude our tour by doing a residency for a few days in Nagoya. There, we will also create new works for the exhibition in September, participate in a symposium, and collaborate with the local community in a workshop. During the take over we will be posting our daily practice as collective; our creative process, how we live our daily lives as a collective and our activities during our stay in Nagoya.”

Adi

Pangrok Sulap

Artist’s bio

Founded in 2010, Pangrok Sulap is a Malaysian collective of artists, musicians, and social activists with a mission to empower rural marginalized communities through art. “Pangrok” is the local pronunciation of “punk rock,” and “Sulap” is a hut or a resting place usually used by farmers in Sabah, Borneo. Since 2013, woodcut prints have become the Collective’s main tool to spread social messages, through large-scale exhibition works as well as handmade merchandise. A strong element of Pangrok Sulap’s process is community participation. The Collective collaborates with community members to collect indigenous narratives and experiences to spread awareness through their artworks.

Members of Pangrok Sulap

1. Rizo Leong

2. Adi Helmi

3. Awang

4. Memeto

5. Ray

6. Gary

7. Alethia

For a few days you could follow her current artistic processes and how she continues to work as an artist and printmaker today in Ukraine based on the current situation.

- Click here to get to her posts on Grafikens Hus Instagram

- Read more on her webpage

A Letter Correspondence

Now at the beginning,

when we are exploring the endless possibilities of having a digital space where we invited the artist Farida Sedoc to have a digital residency, we are faced with various questions that are and will be relevant to the future and present of Grafikens Hus. Together with the artist, we began to explore different thoughts and realities such as what it means to invite an artist to have a digital residency vs a physical artist in residency and what it means for one’s artistic processes? Another aspect that was raised was, what happens to the material that is collected and works that are created? Grafikens Hus is in a phase where we are developing and reviewing what it means to build an art collection when we don’t have one. What does it mean to archive and materialize one’s artistic processes in relation to an institution and one’s own practice? Why archive?

These were some of the questions that were discussed between Grafikens Hus and Farida Sedoc. In dialogue with Sedoc, Grafikens Hus invited the artist and lecturer Catherine Anyango Grünewald to start an exchange of letters where they could correspond based on the questions that came up.

Quote: “I have very mixed thoughts on the idea of an archive. I feel an archive is a highly selective slice of something huge which cannot be adequately described by that particular selection.”

x Catherine

PART 1

Digital vs physical artist in residency – What does it mean for your conceptual and artistic processes?

Farida Sedoc:

When Grafikens Hus invited me to do a digital take over in the beginning of 2022 it excited me a lot.

But also confused me by questioning what this experience could mean in a digital space and in time. Where no specific physical resources are provided except being asked the question to do a digital take-over and our talks about the undeniable existence of social media and its intrusive impact. Long story short I basically became an artist vlogger. And instead of being able to watch it later on YouTube we decided to share my developments of artistic choices in the midst of creating a project to be followed exclusively on Instagram live & stories.

Maybe we should have done it on Tik Tok?

Anyways the idea that the artistic process would only live for that moment in time and could not really be experienced at a later stadium was a strong motivation for me to try it out. When we speak about a physical artist in residency, You have to be there.

With a digital residency, you don’t.

You DO have to be in a space where they have WiFi.

Where “there” can become anywhere and everywhere (where there is WiFi).

This gave me a weird sense of freedom I didn’t expect.

An observation of one’s own art process and exhibiting this in real time.

Even I was surprised of what I actually do in a day where I consciously decide to think and make something.

Capturing how I go about my day, what time I wake up

(waaaay earlier), how I feel.

Now I know

I drink a lot of coffee specifically on these days and don’t like to socialize as much. Trying to get into the zone like I imagine an athlete would do. Hyper focused preferably no one talkin to me unless spoken to. Going through an itinerary I made the day before and executing the steps like a soldier. It’s not fun at all but I felt at peace every step, sure or unsure. Quickly I got into the process of taking pictures of every step I made on my way.

This way at the end of the day,

people who looked at the live and or story would have an accumulation of still and moving images to interpret “my” (is it when you share it while making?) or an artistic experience.

Of course, we see this every day on the app and in a way purposefully share well curated images and messages with a sudden audience. Still, it was new to me in this context and a fun element to consider.

It became part of the work as it developed, because now I had this voyeur in the mix. Now it was an extra lens which made me work more continuous.

Also quicker, mid-week I was further than I expected to be, so it pushed me to make more decisions sooner. The people in the workshop speaking to me I involved in the work by taking a picture of them working in the space or speaking to them in the live about contemporary printmaking and its meaning to them.

Grt. Farida

Catherine Anyango Grünewald:

I’m a little embarrassed

to say that in my whole artistic career I have never been on a residency until now.

I have always been constantly busy with projects and teaching and the idea of ‘time out’ has always been foreign to me. But I did have one small period of extra time where I experimented with my practice and the work I did then, when I was free from expectations, ended up being the basis of all my work now.

So,

in a sense I created my own mini residency without knowing it.

Now I have a residency at IASPIS in Stockholm. It has made me think a lot about the idea of ‘artist spaces’ and how the spaces that artists inhabit or are seen in, such as galleries or private views, are often uncomfortable or exclusive somehow. They sometimes can seem disconnected from the actual process of making the work, and the idea of the relationship with the artist as a maker can be abstracted.

And the pace of being an artist is absurd,

work takes long time,

slow time, do develop and ferment and become,

but it seems that everyone else is always exhibiting and achieving and creating FAST.

When I started at IASPIS I was very nervous about achieving a certain goal in a certain time. But I realized that these residencies are designed to allow you to slow down, to be free of expectation and therefore to allow something good to happen.

In May I interviewed the German artist Anna Haifisch about her graphic novel work.

She is very interested in the space of the artist outside of the art world, spaces where where artists can be contained and cared for – she draws prisons, residencies, rehab centres. The words ‘love’ and ‘care’ and ‘mercy’ keep recurring.

She wrote a book during a digital residency called ‘Mouse In Residence’ which is such a great expression of the feeling of being given a residency. The mouse says I’m simply a bad artist! (This residency) will be the end of me!’ And also ‘(During this residency) I want to transform into a different mouse’.

I think that the book encapsulates the feelings of inadequacy every artist feels in that we feel undeserving of this space but also are certain that it will lead to some great transformation in our practice.

Ultimately in Mouse in Residency the focus is not on the art that the mice produce but on the idea of companionship. I think this is an interesting question in the life of an artist. So much of our time is spent in solitude with our thoughts and our actions, with people only participating in the final result. At IASPIS I was expecting to hide myself away for 6 months and emerge with a brilliant new portfolio, but I found that it was a much more social and communal experience, one that I was not used to, but which is very enriching.

x

Catherine

PART 2

What is your perspective on archiving and materializing your process in relation to an institution and your own practice? Why archive?

Farida Sedoc:

Archiving gives hope and speaks about ancestry of time, space, and people.

I’ve always archived as I’m a cancer (astrology stuff) and think about every little thing and how to preserve a memory or a physical object.

These conversations with self I feel is archiving. Most institutions post #metoo, the Corona crisis and the Black Lives Matter movement condemning institutional racism are having these conversations actively again.

My mother’s generation been talking about current topics since the 70s not to forget my grandmother’s

(born,1925) voice.

And still has an educational and financial investment system for artists development which I believe force institutions to keep up with the level of talks we as artists are having every day.

Fortunately, in The Netherlands there have always been and still is a strong presence of activist effort and intellectual minds who guide and show us what it should and could be.

Even tho I sometimes question their understanding and ambition

there is a willingness to think, speak and act on topics that were denied of their existence before.

An important factor must be that people have to be willing to give up their seat. And make space for people who think of other ways of curating, archiving, and working together. Noticeable awareness of historical connections, exploring past and present makes archiving as a topic so interesting.

Different stories can take different shapes, shown and told in and out institutions not only by the institutionalized. Storytelling should not be taken hostage by monoculture but shared across different communities.

Interested in a wider story of cross-cultural exchange through artistic expression combining traditional graphic techniques, material and image and translate them in a way people can relate to and be inspired by

Grt. Farida

Catherine Anyango Grünewald:

An archive as an idea can be interesting to think about in terms of the knowledge it offers us. It will always be incomplete somehow.

Removing objects from their contexts can elevate or obscure their realities. Simply the idea of classification begins to divide and organize, to create separations or connections between things.

Narratives can be implied from the way an archive places disparate objects together in the same context.

The archive is a collection that starts to have meaning in itself that is larger than the parts represented.

There are chance encounters between different artists just by virtue of existing in the same space. New meanings can be extrapolated, and new connections can be made.

“I have very mixed thoughts on the idea of an archive. I feel an archive is a highly selective slice of something huge which cannot be adequately described by that particular selection.”

In a way it is like a gallery – a collection of end points rather than starting points. I am really interested in starting points and middle points and how those relate to the practice of an artist.

At IASPIS on the first day we were given an A4 box

in which to place things for them to keep in their archive.

The archive room is a small room with identical boxes arranged alphabetically. It is like a roomful of colleagues existing across time, and it is a pleasure and a fright to have the same space and importance on the shelf as so many other artists I know and admire. I have looked through these boxes and they have very different artefacts in them.

At the moment I have drawings in the British Museum archive in London. As a space the British Museum is problematic due to the amount of stolen artefacts that they have in their collection. At the same time, it is a huge honor. I often think about the idea of a scholar engaging with this collection and encountering works that sit together, from so many different walks of life, creating their own internal narrative somehow within the museum.

It makes me think of how we navigate information,

of how when things are placed next to each other, they instantly take on new meaning, or change their own internal meanings according to the perspective of the viewer.

I think my archive box will hold all the little scraps of paper from my work, little rough sketches, the edges of drawings that have been neatly masked and trimmed.

Small scraps and fragments.

I think that the archive can be reimagined as something which is related to an ongoing process, something active in time, rather than something static or final.

What if archives were filled with the unmeaningful?

I really enjoy the ‘saved chat’ document that is generated after a Zoom meeting which archives the asides and notes that occur in parallel to the main meeting. I think that is a great kind of archive.

I would love to see an archive of all the detritus, all the everyday things that it takes to make great pieces of work. I think an archive always narrates some kind of history,

but what kind of history does it narrate?

If it is always a narrative of excellence and power, of perfection and conclusion,

we can miss the many moments that make up that excellence.

x

Catherine